From violent, broken prisoner to redeemed man of God and mentor

When Allen Langham was 16-years-old, his star was in the ascendant. He had started training at a rugby academy and was good enough to have caught the eye of local rugby scouts, soon earning him his first professional contract.

But as quickly as his star rose, it was to dramatically fall as he descended into drugs, violence and eventually a "revolving door" of prison sentences that would span two decades of his life.

If it weren't for an unlikely encounter with God in his prison cell, that might have been all there was to Allen Langham's life story. But his incredible conversion to Christianity while still behind bars started the long journey to recovery - a road that, while sometimes bumpy, has been rewarded many times over with the restoration of family relationships, a sports chaplaincy role, and most importantly, his dignity and wholeness.

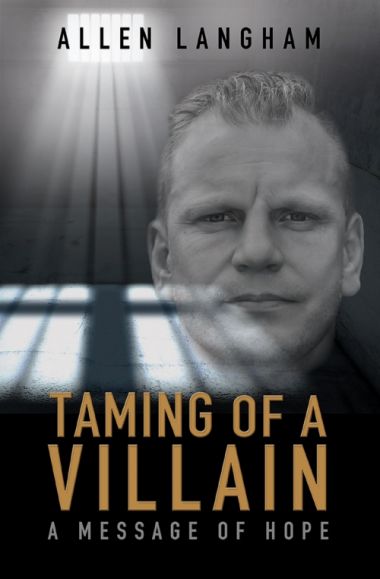

He speaks to Christian Today here about his book, Taming of a Villain, by Lion Hudson, in which he tells his story of how, with God's help, he was able to start again as a father, mentor and man of God.

CT: You are open about your childhood being a struggle. How did that impact you growing up?

Allen: My biggest struggle was not having my father around. He left when I was eight months old and it left a big hole in my life. Although my brother in law was a real positive father figure, he wasn't my dad and I used to form fantasy attachments to my friends' mums and dads, just imagining what it was like to be part of a normal family.

Looking back, I think that was a damaging scenario for a child because I was always craving family and I'd always be trying to mimic the family unit. I think that was the same in prison and with my criminal friends; I was trying to create family but it was with the wrong people.

At a very young age, I became accustomed to violence because I was bullied by older children on the estate where I grew up because my mum was quite old when she had me - she was in her forties - and she wasn't married to my dad. Attitudes were a bit different back then.

But my mum had her own battles too. Her first husband died suddenly in the army; her second husband beat her black and blue; when my dad came along, he whisked her off her feet but it broke her heart when he left her. After that time, she vowed to never be attractive to another man again and so she became morbidly obese.

She suffered from chronic depression, day to day life was a struggle, and she would lose her temper and lash out, so there was an element of violence in the home too. I was on the receiving end of the beatings because my sisters were older and had already flown the nest.

The house was a difficult environment because it was always a mess, there was no food, and so she would become aggressive. But then after lashing out, she would feel guilty and overcompensate by smothering me with attention.

In spite of that, no matter how bad things were at home at times, she was all I knew and I loved her dearly, and I knew that she loved me without a shadow of a doubt. It was just all the other stuff that went with it.

I was devastated when I found her dead from a cerebral haemorrhage. I was 14 at the time but that would shape my life for the next 20 years. If I even thought about my mum, I would think of pain.

CT: What age were you when you started to get involved in crime?

Allen: Within a few months of my mum dying, I was thrown out of school and sent to a behavioural unit. This was where everyone who had been thrown out of school congregated and I started knocking around with older lads who were a negative influence.

Prior to my mum's death, I wouldn't have touched anything but after she died, I gave up a little bit and started to drink and do soft drugs. I started getting into a lot of fights too.

At the same time, I was also playing rugby and getting noticed by a few different professional clubs. When I was 16, I started at the rugby academy and then a youth training scheme with one club, and within a year of that I had signed a professional contract.

With that, I was able to move into my own house, buy my own car, and I met a woman that I fell madly in love with - the mother of my first daughter. But I started going out into the town drinking and spending my signing on money in clubs. That's when it really started to decline.

All the people around me were just as lost and broken as I was and it was like a gang of us colliding together, getting drunk, taking drugs and getting into fights.

CT: What happened with your rugby contract?

Allen: I ended up in court for violent offences and at 18 I got my first prison sentence. That was a massive turning point in my life because I lost my rugby contract. I gave up hope and went into prison. I was like a lost little boy who just needed a little bit of help but in that first sentence, I ended up becoming more criminally minded and I also tried heroin for the first time. It just seemed to melt away all the pain and misery and hurt that I'd felt for all those years.

After I was released from that sentence I ended up going straight back in again for another crime, but there was a brief honeymoon period when I was released from that sentence as my partner at the time was expecting and we'd moved in together and were doing our house up. I'd got some work on a building site and it seemed like we'd turned a corner.

But I fell back into heroin again. I think the things I experienced when I was younger just never got dealt with; the physical abuse and beatings, the loss of my dad. I was also sexually abused by a family friend. It all distorted me.

Everyone around me was telling me to behave and be good and settle down, but I had no idea how to do that. I had all of these feelings inside me that I didn't understand. I think after my mum's death, I just stopped growing emotionally and stopped developing to be able to handle things so that when I reached my thirties, I was still lashing out like a child.

CT: It almost seems like a vicious downward spiral?

Allen: Yes, I started to spiral out of control. Within a year of that time I was a chronic heroin addict living on the streets of London; I had separated from my partner and didn't see our child being born. That was one of the biggest regrets of my life, not being there for my daughter being born. My sister did that role; she was the one who went to the birth.

In 1999, I was sentenced to four years in prison but it was actually a saving grace because it gave me the opportunity to get off the heroin.

CT: Was that because another sentence was a wake up call or because there was help available in the prison?

Allen: No, there was no support in the prison back in the nineties. It was the case of: I'd lost everything - my child, the woman I loved, my rugby, my reputation, my respect.

When I had my rugby, the young people had looked up to me in the community because I was a professional player. But later, there was a big story in the local newspaper with my face on it saying "Heroin Shame".

Heroin destroyed my family relationships. I served 26 months of that sentence and managed to get off the heroin. But there was still the problem of the violence. I actually became extremely violent on that sentence because I had lost everything and got a massive chip on my shoulder. I felt that the world owed me a favour.

CT: At which point did you start to meet God? When did you start to feel some inclination to investigate the Bible?

Allen: All throughout my 20 years of the revolving door of prison, every time I was in, I felt drawn to the chapels. But going further back, as a little boy whenever I was scared, I used to go to the church on my own. No one in my family went but looking back there were some wonderful people who must have seen that broken boy and prayed for him. There must have been prayers going into our lives.

I tried Buddhism, reading the Hindu scriptures, the Koran. I was locked up with a Sikh; I got really into philosophy. I was searching, searching, searching and then on Father's Day, 2008, I found my best friend after he had killed himself. That took me straight back to my mum's death and I knew without a shadow of a doubt that if I didn't do the opposite of what I did when my mum died, I was going to be destroyed. So I went and got counselling and started to seek help.

Fast forward seven years, I was in prison walking around the yard and my enemy was no longer heroin addiction but my violence. I had become like a gangster. I was broken, a mess physically and spiritually. I couldn't live with who I was and I knew that mentally I couldn't do another prison sentence.

Eventually, in Doncaster prison, I visited the chapel and met the prayer ministry team who prayed with me and talked with me. For the first time in that 20-year cycle of going in and out of prison, I felt unjudged and wanted, and I started to go to the Bible studies.

After my release, though, I didn't feel worthy to connect with Christian people on the outside and went straight back to my old ways. I ended up back in prison the day after New Year's Day in 2013 and went straight to the chapel. I just knew that I had to talk with the guys down there and make some changes, and I left that prayer so convicted of my sin and the wreck that I'd become.

Mentally, I'd got to that place where I wanted to commit suicide and had even been saving prescription tablets from other prisoners to take, but instead, I just broke down crying in my cell that night. I was just shaking and such a real mess of brokenness. Between me and God, I just said, 'If you're real and you're hearing me and you're with me, the pigeons outside my window, replace one of them with a white dove.'

I went to bed and got up the next morning, and went to the window as that was where I used to smoke in those days and as the pigeons lifted off, a white pigeon sat down and something inside me just sparked. I just ran out of my cell saying, 'There is a God!' And I committed to Jesus that day.

At that time, I was a failure of a father, a partner and a man, but I was on remand for something I hadn't done. The minister prayed for me that justice would be served and I was miraculously released within the space of a few weeks. That was the last time I was ever incarcerated.

CT: When someone in prison converts to Christianity, what's the reaction like from other prisoners?

Allen: For somebody who's just become a Christian in prison, it's imperative they have resources to help them to be on that journey because, yes, inmates will take the mickey; yes, they'll feel stupid; and, yes, they won't know what on earth's happening.

To make a commitment to Christ is one thing but there's got to be follow through, they need to be discipled. With prison ministry, you are trying to disciple prisoners in an environment where it's designed to fail and that can be challenging.

I was very lucky because after my conversion I got transferred to a different prison where no one knew me. God took me out of that environment that I was in and I remember every day almost tearing the bars to get down to the chapel. As I started to read the Bible, I started to believe more and more, and God started to do this amazing work in me.

CT: How did the decision to believe in Jesus change your life?

Allen: I had had a fearsome reputation - my nickname was 'Bang'em'. But as a new convert, all I could feel was this love pouring out of me. That first night in prison, I read Joyce Meyer's Battlefield of the Mind in which she described balling up the pain of being abused by her father and symbolically placing it at the feet of Jesus. I did that with my rage because the biggest issue for me was that I used to flip out.

I had been diagnosed with borderline personality disorder and was in a bit of a mess mentally when I came to Christ. But I balled up that rage and put it at the feet of Jesus and said, 'You know what, here you go.'

That rage had stolen the best part of my life. By the grace of God, I woke up the following morning with such a waterfall of peace in my stomach. I used to have a washing machine stomach because I was so anxious all the time but that just went and I woke up in the right mind the next morning; the rage had gone.

The biggest testimony to everyone in the community was that this big violent man just wanted to love them and hug them. I had been the kind of person before that people would cross the road to avoid because I would just lash out and punch someone. I could be standing in a pub and someone could just look at me the wrong way or say the wrong thing, or I could even just make it up in my head, and I would punch them or glass them.

But after I came out of prison, I went to the pub and I was praying for the people there. They all just went along with it because they were so frightened of me! But I just had this waterfall of the love of Jesus radiating out of me and I just wanted to pick them up and hug them; I'd been touched by something more powerful than the evil that was around me. People had called me the devil incarnate and all kinds of names, but that was never the real me.

CT: After you were released this time, things went a lot better for you this time round, didn't they?

Allen: Yes, because I had Jesus; I had the answer to all those questions I was asking. Eventually, I came out of prison determined to get my relationships back with my children; determined to get back into my family's life; and determined to get back into rugby. I achieved all three. I managed to have my life ban lifted from the RFL and ended up the head Chaplain at Doncaster Rugby League.

CT: You did end up going back into prison again but for a very different reason, this time to preach. What was that like?

Allen: It's an absolute honour that God can use such a broken man like me, transform my life, and then give me the ability to go in and reach out to the men in the place where I had one time been.

And I tried everything I could to avoid it! Truth be told, I didn't want to go anywhere near the prison. The first time I went back inside, it was a prison in London and I was interviewed by my friend and mentor in front of some of the inmates. It was a really powerful experience and a lot of the men were touched, but I was physically shaking.

I could hear the jangling keys and smell the familiar smells, I could hear the sounds that I used to hear when I was inside before, and I did struggle with it a bit.

But I kept going, supporting the chaplaincy, and it was so powerful. God really just used me in a way I'd never experienced before. The gifts of the Spirit were much more open to me and I was able to share words of wisdom with the prisoners. They would sit there listening and I would ask them to come forward to receive salvation and the whole of them would come forward.

It was so humbling and beautiful and I knew then that there was a calling on my life to reach the people that only certain people can reach, because you've got to experience it yourself sometimes to be able to impact those who are living the same experience.

But I don't think I was quite ready for it at the time because there's something you have to understand about going in to minister in a prison: you're really pressing into the darkest of dark places. And it was stirring up memories and trauma.

When you've been in and out of prison most of your life, you are pretty scared of the place; it has an effect on you. And I did end up taking a couple of years out where I just didn't do anything for the Lord. During that time I felt like He was saying to me, 'You're my project.'

He worked on me during those two years and that was really profound in itself. It was during that time that I actually got the confirmation from the publishers that they wanted to run my book.

With the launch of my book, I'm booked in to do prison talks but this time I'll be going back in as a healed and whole man of God, a man of faith who's been on the potter's wheel for close to eight years now.

CT: What's your message to the prisoners? What is it that they really need?

Allen: Hope. My message is a message of hope, because if you give somebody hope, you give them desire and another chance and dignity. If you give them dignity, you get the man back, and if you get the man back, then there's a chance of him turning his life around. The majority of prisoners are desperately in need of hope and dignity to break the destructive cycle that they are in.

CT: You spoke of how destructive your violence and abuse was to your family. What has the impact of your coming to faith been on your family life?

Allen: I'd never been a part of my firstborn daughter's life but within two months of being released, she came to live with me full time. If she hadn't come at that time, I'm not sure if I would have made it through but I felt such a great responsibility to her to live the straight life and get myself straightened out.

My middle daughter came to live with me around the same time, which was great, and that just left my young son. Because of the nature of the breakdown of my relationship with his mother, I had been told that I wouldn't be able to have any custody of my son until he was 16-years-old. I thought of it like an Abrahamic sacrifice, because I was fighting in court and it was tearing me to pieces; I desperately wanted to be a part of his life. But before the court hearing, I laid my son's life in God's hands and I said 'I don't know what you're going to do or how you're going to do it, but your will be done.' Within six months, I was awarded joint custody.

He was two and a half years old at the time, now he's seven, and he's like my best friend, my little hero; we really are like two peas in a pod. And he's in church, he prays, he loves Jesus and loves people; he's a beautiful young boy with all his life in front of him.

All my children are the biggest part of my life. While the older two have made commitments, they are not actively in church at the moment, but my little boy is desperate to be baptised. In our church, he has to wait until he's 12 for that, but he's already said he wants to be a pastor.

And my sisters and my dad are now back in my life too. Of course there can still be issues; it's not a perfect family. But all these people are back in my life. The impact has been profound.

CT: Speaking about the younger generations, you do youth work too. What does that involve?

Allen: I work in schools and with young offenders. The message is still one of hope, just like with the adult inmates I work with, but the emphasis is on choices - making the right choices and making positive choices, choosing to have positive peers and role models.

I've written a 12-step behavioural course for schools and young offenders' institutes to help young people work through things like trauma. The emphasis is on addressing the core issues rather than managing the symptoms of poor behaviour. I'm hoping it will soon be accredited and that we can deliver it on a more full-time basis. But the main message I want to get across to young people is: think about your choices and make positive choices.

CT: Because it can prevent a lot of the heartache?

Allen: Yes. I just share my life with them and say, 'Look, you don't need to go through all of this to get to where you need to be in life. Don't waste 20-odd years; just skip all of that and come to Jesus now, today, because He loves you so much.'