Dr Who is female. Should the Church take note?

I'll admit it – I'm a huge science fiction fan but not a Dr Who obsessive. I can take it or leave it and most of the time, to be honest, I leave it. My philosophy is, why risk 45 minutes on something that might not be any good when you can be re-reading Julian May's Pliocene saga?

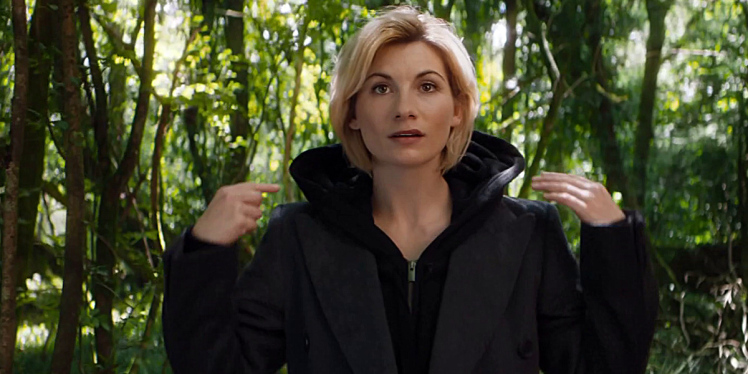

But I do get that for die-hard Whovians this gender thing is a big deal. Jodie Whittaker is taking over from Peter Capaldi, the first female reincarnation in more than 900 years (see? I know about this stuff). For brilliantly witty takes on this, just search #drwho. But I did like Jonny Sharples: 'Your dad thinks Dr Who being a woman spoils the realism of someone travelling space & time in a phonebox fighting bins with plungers on them.' And Matthew Sweet's: 'Blimey. You should hear the arguments in the parallel universe where they've just cast the first male Dr Who.'

Blimey. You should hear the arguments in the parallel universe where they've just cast the first male Dr Who. pic.twitter.com/hu7KFrRTa8

— Matthew Sweet (@DrMatthewSweet) July 17, 2017

Truth to tell, though, pretty much everyone apart from the Daily Mail, which scoured Twitter to find the (relatively few) negative comments about the new departure, was entirely OK with it. Most people are fine. It's fiction, which requires a willing suspension of disbelief, as the poet Coleridge put it; and it's science fiction, which tests that suspension to its breaking point.

No: to find a large group of people who genuinely feel, in these days of female heads of state, CEOs and – well, everything, really – that there are some things women just shouldn't be doing, you have to go to church.

Let's be clear: not all churches. There's a new Bishop of Llandaff who happens to be female. There are lots of female vicars and ministers of various brands. All the major denominations have technically got on board.

In the evangelical world, however, which includes many from these traditional denominations, it's much more of a live issue. The Newfrontiers movement and the FIEC are opposed, and of course the Roman Catholic and Orthodox Churches resolutely refuse to give any groud. But there are three distinct types of resistance and they need to be clearly distinguished.

First, the classical type. Paul appears to restrict eldership and the teaching office to men, and so that's what we should do today. Certainly there are indications his letters to Timothy, for instance, that women were barred from such leadership; one counter-argument is that this was culturally driven and that he was concerned most of all about effective witness. In today's world it's the prohibition of female ministry that's the stumbling block rather than its practice. Another argument along these traditional lines is that Jesus only chose males as his apostles. This was the default position among evangelicals until relatively recently, chiming with a wider resistance in society to women's equality.

Second, modern complementarianism. This is a movement that originated in the US and is associated with luminaries such as John Piper and Wayne Grudem. Its flagship organisation is the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood. There are gradations in how prescriptive its adherents choose to be about what roles are permitted to women (Piper famously expressed doubts about whether women should be police officers as it would mean them having authority over men). But essentially it's a complete philosophy of male-female relationships, in which men have authority in church and in the home by virtue of their gender. Of course it draws on the same Pauline texts, but it also reads Genesis in a particular way. It is, in the eyes of its critics, fundamentally oppressive to women and a prime example of using the Bible to back up a particular socially conservative philosophy.

Third, passive resistance. This is the most subtle kind, and the hardest to deal with. It shows itself, for instance, in the selection of a new minister, when an influential member says, 'Of course we support women's ministry in principle, I'm just not sure the time is right.' Or, 'What would so and so think? They might leave.' Or it's the mental barriers that prevent women in these contexts seeing themselves as potential ministers in the first place, or members of their congregations encouraging them to do so. It's the baggage of generations that has still not been unloaded.

To be clear: I'm deeply unimpressed by arguments for equality on the basis of 'rights' or 'anti-discrimination'. That's not our language. Modernity is temporary, by definition; if we marry the spirit of this age, we'll be widows next week. If we cannot make a case for equal ministry on biblical grounds, there is no point in trying to make it at all – though there is always a dialogue between the Bible and culture. And I have considerably more respect for the classical opposition to women in ministry on the basis that 'the Bible says so' – though I think it is wrong – than for its hijacking by the complementarian social programme. My support for egalitarianism is simply because I believe its critics are reading the Bible wrong. In the case of complementarians, they have erected a massive superstructure on the flimsiest of foundations.

But back to Dr Who. Jodie Whittaker urged fans to 'not be scared by my gender'. Isn't it time for those opposed to women's ministry – both male and female – to ask themselves honestly whether their concern to be 'biblical' (which I do not doubt) has been unduly influenced by something rather less praiseworthy? After all, the Doctor's enemies don't all going around shouting 'Exterminate!' Some of them look quite normal.

Mark Woods is the author of Does the Bible really say that? Challenging our assumptions in the light of Scripture (Lion, £8.99). Follow him on Twitter: @RevMarkWoods