Can Earth's 'bigger, older cousin' support life? Scientists share what they know

The world went abuzz on Thursday when the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) announced that it has discovered an exoplanet, or a planet orbiting a star outside our solar system, that shares a lot of similar attributes with our planet Earth.

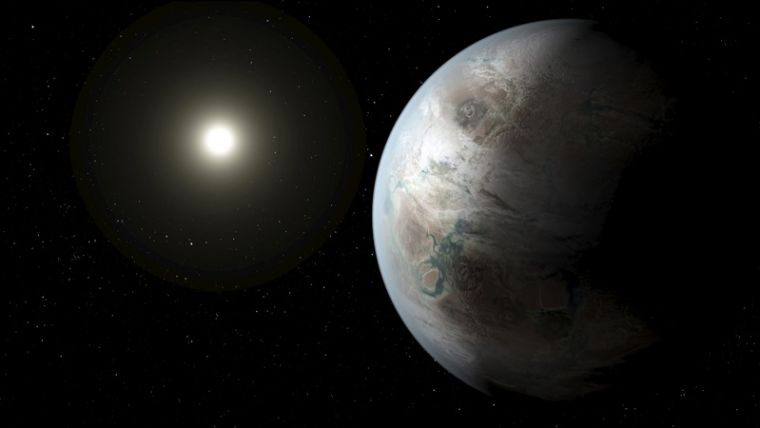

The planet spotted by NASA's Kepler spacecraft, called Kepler-452b, is said to be "Earth's bigger, older cousin." It is about 60 percent bigger than Earth, and is circling a star that is also very similar to our sun.

Following this discovery, the next question that needs to be answered is: Can Kepler-452b support life like the Earth does?

Astrophysicist and planetary scientist Sara Seager from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology explained that for a planet to be able to support life, it has to have an atmosphere ideally similar to that of the Earth, with carbon dioxide, water, and oxygen.

However, due to Kepler-452b's sheer distance—about 1,400 light-years from Earth—not much can be discovered about it at present.

"There's not a lot we can do now," Seager said.

Dr. Doug Caldwell, a SETI Institute scientist, nevertheless theorised that water on Kepler-452b may be running out or not present at all, given the fact that the exoplanet is 1.5 billion years older than Earth.

"If Kepler-452b is indeed a rocky planet, its location vis-a-vis its star could mean that it is just entering a runaway greenhouse phase of its climate history," Caldwell explained.

"The increasing energy from its ageing sun might be heating the surface and evaporating any oceans. The water vapour would be lost from the planet forever," he added.

Another difficult question to answer is: Is there life on Kepler-452b?

"It's quite literally anyone's guess what those planets are like," astronomer Greg Laughlin from the University of California, Santa Cruz said.