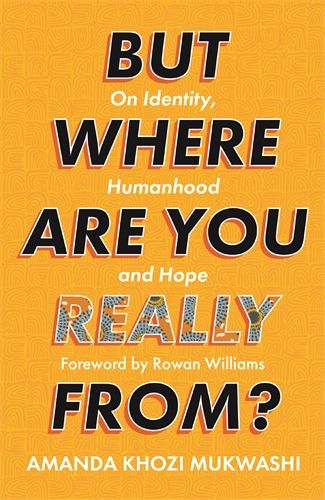

But where are you really from? Christian Aid CEO Amanda Mukwashi on race and identity in Britain

As a Briton of Zambian heritage, Christian Aid CEO Amanda Mukwashi is all too familiar with the question 'But where are you really from?'. So familiar that she chose it as the title of her new book about race and identity.

Published by SPCK, 'But where are you really from?' challenges the often polarising perceptions of others that can foster divisions in society.

She instead encourages Christians and non-Christians alike to think about how these perceptions can be turned on their head to bring people closer together instead of further apart.

Amanda speaks to Christian Today about her book and why she thinks the Church is perhaps better placed than any other institution to make a positive change on the issue of race.

CT: You write in your book that you find this question 'But where are you really from?' quite frustrating.

Amanda: It is a question I get quite a lot and sometimes I hesitate when someone asks it because I am trying to second guess what they want from me. Are they going to be satisfied with an answer that says 'I'm from Coventry' - I was born here but didn't grow up here because my parents moved to Zambia and then we travelled around because my stepfather was in the diplomatic service, but when I returned to Britain, Coventry is where I lived for a very long time.

If I do say to someone that I'm from Coventry, then they will typically say 'but where are you originally from?'. Sometimes I 'play the game' and tell them I was born in London, to which they will then usually reply 'yes, but where are you really from?'. Other times, I just cut to the chase and say I am originally from Zambia!

But it is a question I get asked quite a lot and I find that other people I know who look and sound different get asked this question a lot too. They relate to the question and they know what that question really means.

In fact, since writing the book, people from all over the place have come up to me and said 'I know that question very well'! In the beginning, I didn't really think about how wide a spectrum of people this covered but now so many people have said to me 'oh yes, I have been asked that question'.

CT: It seems to be a universal experience of those who look or sound a little bit different from the majority?

Amanda: If you look different and sound different, then people will naturally conclude that you're not from the four nations - you're not English, Welsh, Scottish or Irish, and that means you're a migrant. Then the question 'where are you from?' becomes more like 'what are you doing here?' 'Were you running away from conflict?' 'Were you running away from poverty?' It can't just be that, actually, I love to travel and I decided that I wanted to come here and contribute positively to this country.

The minute you are put into this box of the 'other', there is all of this baggage that comes with that; there's a burden placed on the word 'migrant', and then the concept of 'migrant' in this country starts to kick in. 'You've come to take our jobs.' 'You're taking up space.' All of these notions start to kick in in a very subtle way.

My son was born here and my daughter came here when she was one so they don't sound different, yet they still get this question 'but where are you really from?'. And they get the question because they look different. They could be third or fourth generation British but because they look different, they will still get asked that question.

Some of my friends have parents or grandparents from the Caribbean, but they themselves have never been there and Britain is the only home they know. So when you are asked 'but where are you really from?', it is essentially saying that this is not your home. Quite a lot of BAME (black, Asian and minority ethnic) people have this identity crisis because on the one hand, they are made to feel that this is not their home. Yet when they go off to Jamaica or Barbados, they are seen by the people there as British.

Several years ago I met someone from Brazil who is descended from Japanese immigrants and so has Japanese features, but his nationality is Brazilian and he doesn't speak Japanese. He told me that when he went to Japan, he stood out, people could tell he wasn't from there, and he himself felt it wasn't his home. And yet in Brazil people always assume he is from Japan. People's assumptions can be very invasive!

CT: Conversations around race and identity are finally happening now in the wake of George Floyd's death. Could this be a turning point in our society in terms of how we view minority ethnic people? Could it be a watershed moment that might make things a bit easier for younger and future generations of BAME people?

Amanda: We could make it into a watershed moment and the point where we turn the conversation around. That opportunity has presented itself. But I think it's not going to happen automatically.

When I think of the Black Lives Matter protests and the demographic of who went out to protest, they didn't come from one ethnic group. They came from a whole section of society and a lot of them were young people. In fact, it reminded me of last year when young people marched against climate injustice.

There's something about the younger generation that won't tolerate any form of injustice. They by and large don't want to be part of a world that is predominantly unjust, and I think that is the opportunity that we have to turn the conversation around and bring about change.

Young people are not afraid to express themselves, and they're not apologetic about their views and calling out injustice, so there's a real opportunity for us. But the reason why I'm saying it 'could' bring about change rather than it 'will' is because the people in positions of power and authority are still of the generation that is comfortable with the status quo.

If we choose to remain silent, we could end up frustrating the conversation. We need to actually stand up and say: on climate change, on racial injustice, on poverty or whatever the issue is, let's make space for a change, let's be part of the change rather than obstructing the change.

It's interesting to hear what the politicians are saying. Are they coming out and saying that injustice is wrong? No, they're not. We have the likes of Donald Trump not taking a clear stand on the far right and racist groups, and it's that kind of politics that's going to stand in the way of us turning things around.

But it's not just in the US; it's here in the UK too. There have been conversations around changing the curriculum so that children can learn about history from a different perspective. But instead of politicians embracing that idea, we hear them saying 'no, we don't want any changes to the curriculum'. That is the attitude we need to turn around for future generations.

CT: In your book you say 'enough is enough'. Do you think that sentiment is widespread in the black community and that this is perhaps why such large numbers have come out to protest against racial inequality?

Amanda: While I can't speak for all black people, I certainly feel that enough is enough and I think there is more and more a sense of that. But I'm also coming from a spiritual perspective as a person of faith. I know that God answers prayer and I personally have been asking God the question: God, when are we going to see a change for black people? Because they have suffered and struggled for generations. This isn't something that has just started, it's been going on for hundreds of years. And the current economic system and the global power dynamic means that it is those people who are black and of darker skin who are continuing to suffer.

There is that part of me that says 'you know God, we need to see you; we need to hear you; we need to see the miracles of change'. During the current pandemic, I've joined a number of prayer groups with black people joining in from all around the world, and the sentiment is the same: God we have suffered enough. The difference I see is that the older generation will say 'enough is enough' but it is the younger generation who really want to do something about it.

Young people want tangible change and action, and I feel absolutely inspired by them because they are standing up and saying 'this is my home; I'm not originally from some other place; this is my home and I want a place for myself in my home and I want to contribute like everybody else to the place that is my home'. Kudos to them for doing that.

Interestingly, it is the resurgence of the far right that has exposed the complacency of our global leadership and which has therefore also galvanised people to say 'no more'.

CT: Perhaps white people could look at this question and think it's an innocent question?

Amanda: When I was writing the book, I wanted to test how other people felt and one of the people I spoke to was Rowan Williams, who wrote the forward to my book. He observed that if the question were to be asked to him by somebody from Wales, where he is from, then the intention behind the question would be to find that connection between themselves. So, the question 'where are you from?' when asked within communities is really about finding common ground.

But when someone like myself is asked that question and I get 'no, no, no, but where are you really from?', then it's no longer about finding a connection and including me; it's more about excluding and othering, and all the judgements that follow on from that.

CT: How can we as a society move beyond simplistic ideas about identity?

Amanda: When I worked for the UN, I met so many people from different parts of the world and from different cultures. I became so used to people speaking differently and sharing different ways of doing things, and I could see the beauty in those other stories and in other people's cultures. I was in Russia one time and the mainstream media loves to tell us that Russia is a monster. But I went to a rural community where I discovered that volunteering was so ingrained in their culture - and not just once a month, but regularly. It was so ingrained that they didn't even call it volunteering because it was just a normal part of life for them. They had a wonderful way of coming together and socialising and eating together.

What I started to realise was that actually every single culture and people group in the world has got some beautiful things. They can have some horrible things, but they all have beautiful things about them.

If only we could have the mindset that says there is something beautiful and worth preserving in every single group of people, and that there's something worth learning from as well. I think then we would begin to really change the way we see each other and the world. At the moment, it's either that the Russians are bad, or China is bad, or Zimbabwe is bad, and these other people are good. There's no middle ground. There is no in between that says, you know what. there's a lot more to us than you think.

The media plays a critical role in how we perceive other countries and other people, but the mainstream media hasn't always done us any favours in this respect. And what I see now is young people finding an alternative narrative on social media. Young black people are finding these stories of black people who have achieved and enjoyed success. They don't need to listen to the mainstream media telling them there is only one story. They can go elsewhere now and find role models and mentors, and be encouraged by their stories of success.

CT: In your book, you note the international ramifications of our notions of identity when you observe, for example, the indifference about the Amazon fires. You write: "who cares if the people of the Amazon forests are threatened because of the fires? They are indigenous people of black origin so their lives are graded as less important."

Amanda: Our understanding of identity has international ramifications but it also has life and death implications. When we look back into history, the Church and human conscience so brutally viewed Africans as a product because in their minds, they had degraded them to such an extent that they were able to justify treating them like animals. That is why African men, women and children were sold and traded in the marketplace as if they were dogs or cows.

Just because they are no longer being bought and sold in this overt way doesn't mean that the legacy of slavery has disappeared. It has simply translated into a mindset that continues to see others as 'less than'. So when we take this question of the Amazon, we have a situation today where the cutting down and selling of trees has become much more valuable than the people who live there. When Notre Dame went on fire, millions were raised in the first 24 hours. Of course, it is a historic building; no one is denying that. But contrast it with the plight of the people in the Amazon, whose very existence is threatened. We had to go out and launch an appeal, and it was only down to the generosity of our supporters who then enabled us to help these people and work with them.

So, we are no longer openly selling people on the slave market and yet, we are still treating some people as second class human beings. We are not valuing their story and saying that this matters, that who they are matters, or that where they live is important, and that they are part of our social fabric and the social narrative of the whole of humanity. It is in this way that the legacy of slavery continues.

CT: Do you think those attitudes are there in the interplay of relationships between powerful nations and poorer countries that remain in debt?

Amanda: It manifests itself differently but it's part of the same thread. If we look at the debt issue, poor countries keep on borrowing and as they borrow, they are able to spend money for basic infrastructure. Don't get me wrong, those developing countries do have a responsibility in terms of their own governance; they need to be held accountable and they need to take responsibility. But at the same time, they are running in a race that starts from negative equity.

For example, a devastating humanitarian situation arises in Yemen and so the government decides that it is going to give some aid to Yemen. But at the same time, the government sells arms to Saudi Arabia knowing full well that Saudi Arabia will use those arms to go and kill people in Yemen. If Saudi Arabia was planning to use those arms to go and kill people in Germany, I think that equation would be different. But the life of a Yemeni is not as valuable, and the money that comes in through the arms sales is much more than that being spent on the aid going to Yemen. At the end of the day, the bottom line is self-interest and a kind of 'any cost' reasoning that says 'as long as this doesn't affect those who have the power'.

All of this can sound as if nothing good is happening and that's absolutely not true. There are good things happening and I work with a lot of people who are doing everything they can to try and make things better. Some have dedicated their entire careers to challenging the power structures, economic systems, and exploitative, discriminatory practices.

These people can be found in charities like Christian Aid but they are also in governments, in multilateral agencies like the UN, and yes, in organisations like the IMF or the World Bank too. There are good people working in all of these different places trying to see if they can beat the system to bring about real change.

But the challenge lies in the fact that the institution has been created in terms of economic might and power, and is one that exploits poor countries and poor communities all the time. Even when you look at climate change, for example, while we here are busy having a conversation about whether it is happening or not, in Ethiopia they know it is happening. The people there are already seeing it and feeling the consequences of it first hand.

CT: Going back to the issue of racial inequality in society, what role do you think the Church can play in being a voice for positive change, especially in light of its own complicated history with racial inequality?

Amanda: I think out of all the key actors, the Church is perhaps better placed than anybody else to try and make a change, but it will come at a cost. The message in the Bible and the Gospel of Jesus Christ is very clear. It is one of love; Jesus Christ came to reclaim that which had been stolen for his Kingdom. He was the sacrificial Lamb so that the children of God could have that opportunity to be redeemed. God had a plan of redemption and I think that's who we as Christians should be. We should be here to manifest what Christ manifested for us.

But take the disciples, for example. They didn't build big institutions of power in order to talk about the love of God. They had very little in terms of material wealth and yet they went out and the Gospel spread a lot during that time. What the Church has done instead is to have created institutions in the mirror image of secular institutions of power, so that rather than creating institutions in the mirror image of Jesus Christ, who we follow and who didn't have anything material for himself, our religious institutions are now based on secular models of power. In that way, our church institutions have become places of power, and as soon as they become places of power their job becomes self-preservation.

What's the difference between the Church as an institution and the Government as an institution? The Church makes laws for its people, it creates regulations, it has businesses, it invests in fossil fuels. It almost functions like a political institution and that is how it preserves its power. That's not how it preserves the Word of God and faith, and that's why we've seen over the last 10 to 15 years people no longer trusting the Church. But it's the institution that they don't trust, not the word of God or faith.

Therefore, if the Church goes back to the Bible, back to Scripture, and back to its original message, it will be easy for the Church to give up some of that power. The only power we need as Christians is the power to liberate the oppressed and provide for those who do not have. But the power we currently have as the world Church is sometimes scary! So as long as it's about power, we're lost. But if we can just start that conversation again and build the Church in the image of Christ and his work and his approach and methodology, just think what it would look like.