After Wonga: How Christian values are helping reshape Britain's relationship with money

Some five years ago, Justin Welby, the newly enthroned and 105th Archbishop of Canterbury, gave a typically candid and convivial interview to Total Politics. Politics, sex and The West Wing were on the table. So too was his campaign to tackle the invidious effects of high cost and exploitative payday lending.

Would the Church of England hector? No. It would invite churches the length and breadth of England to throw open their doors and welcome in credit unions offering the alternative of mutual saving and borrowing. They were money lenders, and they were being invited into the Temple. But they were not profiting unduly from usury: their rates reflect the cost of lending; they promote saving, not least as a way to reduce reliance on credit; they help and advise customers – even, very often, those who cannot afford to borrow.

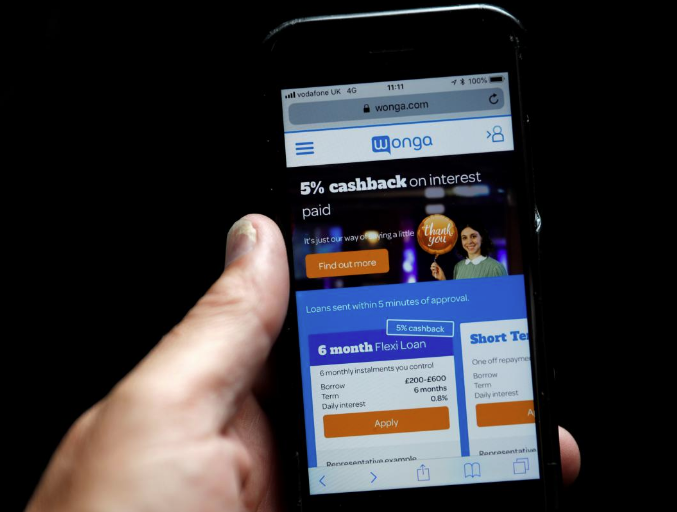

The Archbishop recounted his words to the chief executive of Wonga, one of the largest and most brazen payday lenders whose annual interest rates could be as high as a truly disturbing 5,385 per cent: 'We are not trying to legislate you out of existence. We are trying to compete you out of business.' More Pied Piper of social change than pugilist.

But what happened next threatened to change all that. 'War on Wonga', the morning papers raged from their front pages. The contest had become a battleground, and the archbishop had been tasked with leading the charge. Such were the birth pangs of what was to become the Just Finance Foundation, the archbishop's charity focused on fostering a fair financial system.

On closer inspection, promoting financial health, of the many struggling with debt right across the social spectrum, and particularly among those for whom making ends meet is a daily struggle, was found to be complicated. Credit unions and other responsible finance providers face significant barriers to scale, the combined value of their loan book representing only one fiftieth of that of the high cost credit sector. The people who need help most are often least likely to come forward – five in six who are over-indebted do not seek help (it turns out not everyone shares the archbishop's ease in talking about money – in Britain, it is even more stigmatised than talking about sex).

Furthermore, the UK has an endemic problem with financial capability. A recent study of developed economies by researchers at Cambridge University and UCL, for example, ranked the UK among the bottom four nations, with one in three adults in England and Northern Ireland unable to make everyday financial calculations such as working out change. Half the population lacks savings of more than £100, a sum that leaves you pretty exposed when a washing machine packs up, a car tyre needs replacing or you need a deposit to rent a house.

The archbishop did support calls for the regulator to cap charges on payday lenders, and listening in five years later, his endorsement is still credited with being influential. Charges were capped at a total of 100 per cent of the sum borrowed. A million consumers were said to benefit. Several payday lenders went out of business. For its part, Wonga's profits halved in 2013 and losses doubled in 2015 to £76.5 million after tax. The exploitative business model was broken. And now we see Wonga in administration.

Meanwhile, with the help of the Church Urban Fund (CUF) and its partnerships with over Anglican 20 dioceses from Plymouth to Bradford, the Just Finance initiative incubated practical programmes to address gaps in action on financial injustice and distress. The Just Finance Communities programme works on all the 'last mile' issues of making fairness a reality. Staff and volunteers amplify the piper's tune, equipping local groups to raise awareness of the extent of financial distress, its impacts and to invite action. They increase the availability and awareness of responsible finance, sometimes recruiting volunteers to run counter services in neighbourhoods that lack financial and other services, other times to promote products tailor-made for low income households, or broker significant payroll services with local employers, mergers and investment.

This is never just about the money. It's always about lives. What was it that broke one of our earliest customers and sent her debts spiralling? The simple desire to provide her daughter with a school uniform and a pair of shoes.

On the demand side, the Communities teams play a distinct role that deserves to be an integral part of realising the aims of the national financial capability strategy. They reach and engage people who are far from ready to identify with money specialists, give them a taste of what it feels like to regain control of their money, and grow their motivation to confront remaining challenges – through their own initiative or with other agencies.

Independent evaluation of the Cash Smart Credit Savvy programme has demonstrated that 94 per cent of participants intend to plan how they will spend money, and just under three quarters spread what they have learned. Since all of us, on money, health and a host of other issues, give greater credence to what we hear from family and friends than experts, this seems to be a particularly important contribution.

The other programme, LifeSavers, enables primary schools – around a hundred to date – to embed financial education. Watching children grapple with the emotional and social implications of decisions at the same time as the maths and lexicon of money (council tax, anyone?) inspires hope that we really can create a generational shift in our relationship with money. Children engage deeply with purposes and what choices mean for them. They regularly prioritise long term benefits, like growth in savings over the bait of incentives on junior savings accounts, defer short term gratification and demonstrate generosity to their parents, siblings and friends – saving for birthday presents, for example.

The programme builds teachers' skills and confidence at no further cost, too. So, while surprising given the usual concern about central edicts, staff workloads and schools finances, 70 per cent of LifeSavers headteachers would like financial education in primaries to be mandatory.

Both programmes illustrate how capitalism can (and should) be in service to a value system that recognises humanity, that is, each individual and each community with whom their wellbeing is entwined. They appeal to people's aspiration and commitment and build stronger alliances. They achieve their goals through respectful and good quality relationships.

Christian values inspire the ends and means of Just Finance – though it is not a Christian charity, its activities are open to all and it does not proselytise. But they are also widely shared and can inpire others too.

So far, so good. But what for the next five years? Growth, obviously. Just Finance has been rigorous in testing and evaluating its programmes and they need to be scaled to meet the needs of a growing number of households in financial distress. But in establishing new aims for the newly incorporated charity last year, the board also returned to the vexing question of fair and affordable credit.

Wage stagnation, the growth of the gig economy and the questionable ability of benefits to enable people to meet their costs all mean the pool of people at risk of financial crisis continues to grow.

The Financial Conduct Authority is to be congratulated for cracking down on other kinds of high costs credit – though this limits sources of credit for people who depend on it – and is considering how financial inclusion can be better served by the mainstream retail banking model. Modest fees for current accounts, as they charge in parts of Scandinavia, that cross-subsidise services for low income consumers, is one idea that's overdue.

The government has designated £55 million of assets from dormant bank accounts to improve financial inclusion, and ministers and officials have so far been consistent in saying they seek 'scale and sustainability' in the growth of and access to responsible finance. This is where Just Finance can do more to help. Now that leaders in banking and regulation sit round the board table with church and community leaders, financial and innovation experts, Just Finance is bringing together banks and other investors, responsible finance providers, intermediaries and policy makers to design how mainstream capital, of perhaps £100-200 million, can be used to scale up responsible lenders.

There is a rising tide of action on just finance. Now it's time for government to tell a bolder story, chart a bolder course, and make a commitment to ensure affordable credit for all within 20 years.

Rowena Young is the executive director of the Just Finance Foundation.