Why Britain should be proud – and protective – of our aid budget

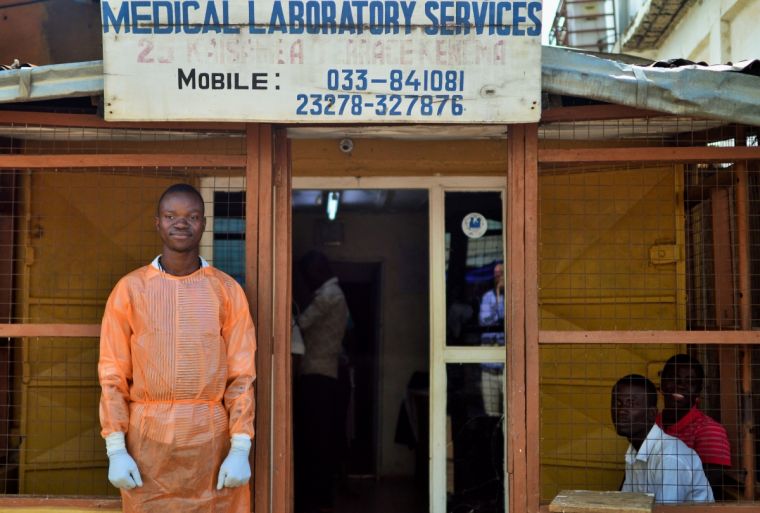

Last month, standing in his late father's laboratory in Kenema, Ebola survivor and orphan Douda Fullah asked me if he could give a message to the people of the UK; to the people who helped him when he lost most of his family to the deadly Ebola virus that swept West Africa.

He said: "On behalf of all the orphans in Sierra Leone I want to say thank you to all those who, in diverse ways, supported Street Child to lift hunger from the homes of orphans of Ebola. I want to say bravo, thank you and God bless you. You have done great things, even though there is more to be done. God bless you all."

Yesterday, MPs debated whether the UK was right to ring fence 0.7 per cent of GDP for foreign aid. The debate was the result of a 200,000 strong petition started by the Mail Online to question whether we should spend so much on helping people who do not live in the UK.

Douda told us that without Street Child, he might be homeless right now. He wouldn't have been able to care for his little brother Richard and make sure that he could go to school, or have been able to take on the family business as he is now.

Douda is one voice, albeit a voice that became widely heard after he gave an anguished interview at the height of Ebola that was broadcast around the world. Street Child, hugely supported by UK Aid, has helped more than 11,000 Ebola orphans in Sierra Leone.

It is undeniable that there is a strong biblical imperative to support the poorest, to look after the widow and the orphan. During the Ebola outbreak we saw first-hand why that is so important, and the tragic consequences of what happens when you do not.

We heard about two toddlers in Monrovia who were living alone after their parents died of the virus. Their community were too scared to visit them, and the children were starving. Sadly, our team heard about them too late – when they arrived with emergency food supplies, the children had already passed away.

Yesterday, Christian MPs made an impassioned defence of maintaining support for the world's poorest people. MPs Stephen Doughty and Dr Lisa Cameron spoke about their faith as a key driver for why they believe it is the right moral response.

Cameron said: "As a Christian, I believe we have a moral duty to fulfil our commitment to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals around the world. As humans, we share one planet and we must contribute to making it fair, healthy and safe for all."

My personal faith is at the heart of who I am and thus at the heart of why I started and run UK NGO Street Child, but whether you're motivated by moral arguments or not, what we saw repeated time and again in last night's debate was the argument that more than just being moral, giving aid makes sense for the UK.

Doughty said that while as a Christian he is ashamed of the poverty he sees abroad, it is actually in our interests to tackle the causes. He pointed out that diseases like Ebola don't respect borders, and therefore present a global threat.

Another story, that of Finda Nymah, a grandmother from Kpondu village in Sierra Leone who was the first victim of Ebola in the country, makes this stark point – challenging the idea that overseas aid is just a kind, moral idea.

Her death in May 2014, a tragedy in its own right, led to tragedy on a vast scale. The World Health Organisation estimates that her funeral alone led directly to 350 deaths from the virus.

Over the following two years, Ebola spread far beyond the small, remote village of Kpondu on the Guinea-Liberia-Sierra Leone border to claim almost 4,000 lives in Sierra Leone, and leave 12,000 children orphaned. It marked the start of the deeper region-wide Ebola crisis and caused a global health emergency.

The incredibly low levels of healthcare and education in the three worst hit countries were the key underlying factors behind the spread of Ebola, putting other countries at risk and requiring huge sums of international aid to be spent to control the virus.

It revealed how the illiteracy of one person was not just their own personal problem or tragedy – it was something that could have dramatic consequences for all of us. Illiterate people who engage in dangerous health practices do not just endanger themselves, but can unwittingly put lives at risk on the other side of the planet.

Finda lived in a cluster of 12 villages where there has never been a school. It's actually not difficult to avoid Ebola – don't touch ill or recently deceased people. But if you don't have the educational ability to receive, or scientific understanding to trust, this message you are at grave risk. And as a result, to some extent, so are we all.

Today, builders in Sierra Leone will be working on Kpondu's first school, built by Street Child with funds donated by the British public and government. The school means that Finda's twin toddler granddaughters will have access to the education that could have saved their village, and Sierra Leone, from Ebola.

As Stephen Timms MP highlighted when he spoke about the importance of education for all, this is not just good for these girls – it is good for everyone, wherever they are.

DFID is currently match funding all donations to Street Child's Girls Speak Out appeal which aims to help 20,000 poor and Ebola-hit children to access school this year. Programmes like this, investing in stopping these children from becoming a lost generation and giving them hope for life, change lives over there, but also make us that bit safer, here.

Of course there are rightful questions to be asked about how aid is invested – after all, badly administered aid helps no-one – but what the Mail's debate has actually revealed is the depth of cross-party support for helping our international neighbour.

And it is heartening that Christian MPs were at the forefront of standing up for the poor, the widow and the orphan, so that people like Douda can have a hope for the future, regardless of where they are from.

Tom Dannatt is CEO of Street Child, www.street-child.co.uk.