Whatever happened to laying down your life?

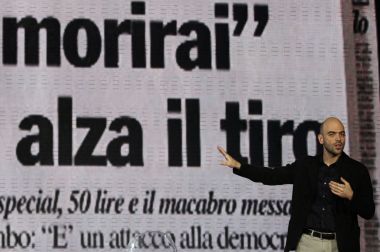

Roberto Saviano is an Italian journalist and author, best known for his book Gomorrah. He's received worldwide acclaim for his documentation of organised crime in Naples. He's a hero to journalists worldwide and a frequent VIP at literary festivals, major conferences and media gatherings.

His life, however, is effectively over as he once knew it. He broke no laws, and received no sentence, but he has given up the chance to live in freedom.

Because he told the truth.

In a phenomenal first-person essay published last week, Saviano talked candidly about his life under armed guard. He's permanently protected by a crack team of seven bodyguards, who spend their lives checking under cars for bombs, or ensuring no-one knows which hotel room they've checked him into. This is all necessary because Saviano not only blew the whistle on organised crime in his hometown of Caserta, but publicly shamed the mafia bosses he was taking on. In a town and a city infamously riven with corruption, his book was simply too popular and influential to be ignored. The powerful Camorra clan - the target of Gomorrah - made it very clear that the writer would pay for daring to shine the spotlight on them. He was a dead man.

Nearly a decade after the book's publication, Saviano is still very much alive. Yet his life, he says, is ruined. "It's hard to describe how bad it is," he writes. "I exist inside four walls, and the only alternative is making public appearances. I'm either at the Nobel academy having a debate on freedom of the press, or I'm inside a windowless room at a police barracks. Light and dark. There is no shade, no in between." Circumstances have changed him, he says. He's a different person; "[I'm] probably a worse person," he claims. "More withdrawn, detached, because [I'm] constantly under attack."

He questions whether he'd do it all again, knowing what he knows now. Saviano was motivated to write Gomorrah not by the lure of a publishing deal, or critical acclaim, but because he could no longer stand by and watch the injustices perpetrated by the Camorra in his home town. As a young reporter in Caserta, he says he would report on "two or three murders a day", as well as arson attacks, people being shot in the street because they looked like the intended victim. "It was incredible that something like that could be going on in the middle of Europe", he says.

So he was faced with a choice - to fall into line with every other reporter, police officer and government official in his town, and turn a blind eye, or to do the unthinkable, and stand up to the mafia.

As I read Roberto Saviano's story I was gripped. It's increasingly hard to hold a reader's attention in a long-form online article, but I stayed with it to the very last word. What surprised me however was how it stayed with me; how it challenged me; how it nagged at the very heart of my life and faith.

In Matthew 16, Jesus is explaining the cost of following him to his disciples. "If anyone would come after me," he says in verse 24, "let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me." He then explains that concept of 'taking up a cross' in John 15: 12-14, when he tells them: "This is my commandment, that you love one another as I have loved you. Greater love has no one than this, that someone lay down his life for his friends." There is a core element of the Christian faith that demands self-sacrifice; a laying down of our lives for what's right.

Roberto Saviano saw rank injustice, and was presented with that same conundrum. He could either stand by like everyone else and turn a blind eye to the sin of the world, or he could take the narrow, painful path of self-sacrifice, and in so doing effect immeasurable good. Though I don't know that he was motivated by religious faith, his choice is a picture of putting those challenges from Christ into action.

By contrast, my life, which is highly motivated by religious faith, looks nothing like this. I can't think of a major decision that I've made in my life on the basis of my beliefs which has significantly impacted my ability to enjoy a comfortable lifestyle. I've made small, moral decisions that might have prevented me from having a little 'fun', and I've attempted to live a 'good' life. But I've never been called on to truly 'lay down my life' for what's right, for the sake of others. Or at least, I haven't heeded that call.

If we're really honest, what really niggles is the question of how we might respond if God really did require some sort of painful sacrifice from us. Perhaps a comfortable, cuddly faith housed in a middle-class life may not be the healthiest, the most dynamic, or the most prepared for action. In Galatians 2 v 20, Paul writes "I have been crucified with Christ. It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me." If that was really true of our lives, wouldn't we live a little differently?

Which provokes more questions. Shouldn't more of us be moving out to remote parts of the world to become missionaries? Or selling our houses and giving all the money to the poor? Why does it feel like 'news' when someone actually responds to Jesus in that way? And how might the world view Jesus and his followers if we all suddenly started behaving like that again (see Acts 2:42-47), rather than living a slightly nicer and lower-alcohol version of everybody else's life?

Of course, following Jesus in an attitude of self-sacrifice isn't just about grand gestures - although we should be more comfortable with this idea that it might be. Luke's version of that conversation with the disciples uses the words 'take up his cross daily', and while that's potentially even more frightening, it does suggest that there are scores of ways, every single day, that we can practice the love of God and the presence of Jesus through acts of submission and self-sacrifice. Putting someone else's agenda first, showing generosity or hospitality to a 'stranger', or taking the time to stand up for someone else; these are all small ways in which we can be people who defy what's wrong in the world, demonstrate self-sacrifice, and take another pigeon-step in the path of Jesus.

Roberto Saviano's closing words for The Guardian are compelling, and undeniably spiritual. "If I have a dream," he says - and in context, he really means prayer, "it's that words have the power to bring about change. In spite of everything that's happened to me, my prayer has been answered. But I've become someone different than I imagined. This process has been painful, I've found it difficult to come to terms with, until I accepted that none of us is in control of our own destiny. We can only choose how to play the role we are given."

All of us, in big ways and small, choose whether we want to be Mafia whistleblowers or complicit in the evils of the world. In reading Saviano's words, I'm reminded that when we decided to follow Jesus, we implicitly made that choice too.