The legacy of the 'war on terror': a more dangerous world and the loss of moral high ground

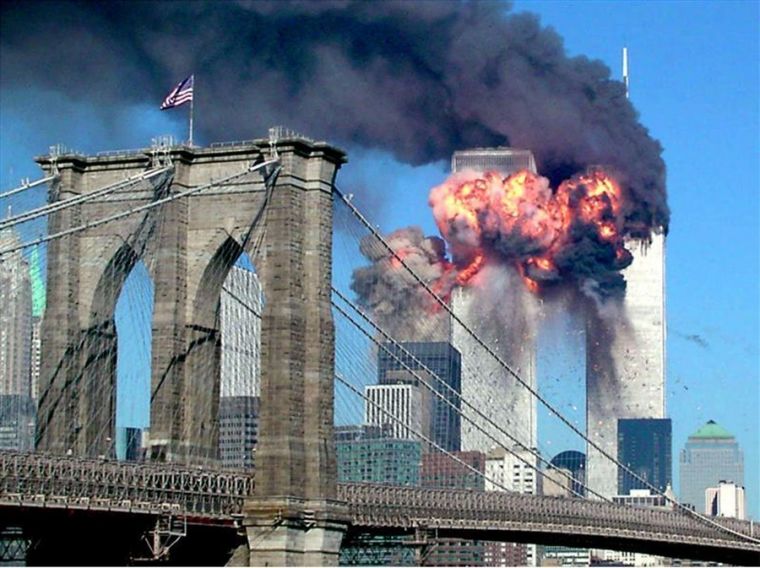

The atrocity of September 11, 2001 was the formative event of my lifetime. No-one who watched live as the second plane flew into the Twin Towers in New York, will ever forget the sight.

But it was not just the shocking images that were implanted into the mind. It was also the desire for a proper response.

Just as you didn't have to be a foreign policy 'hawk' to support the idea of military and diplomatic reprisals, you did not have to be a 'dove' to oppose the cornerstone of the subsequent reaction: the invasion of Iraq.

It is 15 years to the day since George W Bush launched his "war on terror". In a landmark speech to Congress nine days after the attacks, he said: "Our war on terror begins with al Qaeda, but it does not end there. It will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped and defeated."

At the time, it was virtually impossible to argue with that, and Bush – along with Tony Blair, who stood "shoulder to shoulder" with him and flew around the world acting as his unofficial envoy – had a huge amount of international goodwill.

Yet meanwhile, within days of 9/11, Bush and his team were attempting to find a link between that event and Saddam Hussein's albeit barbaric but broadly secular regime, a regime that – then – had nothing to do with al Qaeda or its leader, Osama bin Laden.

The drum-beat to war on Baghdad lasted only until March 2003, when the US and UK launched their hastily planned and disastrous "shock and awe" war. As a response to 9/11 it was, for want of an infinitely stronger word, wholly inappropriate.

Arguably, the previous war in Afghanistan, from which the Iraq adventure drew resources, was an ill-advised reaction too. True, there were reportedly al Qaeda training grounds in the notoriously treacherous terrain of Afghanistan.

But wiping out the Taliban was never a realistic aim, and meanwhile it appeared to escape the notice of the West that some 15 of the 19 suicide hijackers from that day were from Saudi Arabia, which to this day mysteriously remains a key ally of the US and the UK. Yes, the Saudi regime claims to be battling against al Qaeda itself. But what bigger event could there have been to instigate a rethink of relations with this anti-democratic, oil-rich nation?

If that was too much to ask, was there not a case for the West retaining the moral high ground which it lost with Iraq, Guantanamo Bay, Abu Ghraib and other war crimes, by simply treating the hijackers as the low-life criminals that they were and, when it came to a military response, turning the other cheek?

Instead, the US launched two bloody wars, the implications of which, despite the withdrawal of US and UK troops, are far from over.

Yes, bin Laden has finally been killed, as have a range of other terrorist leaders. But on its own terms, Bush's mission outlined 15 years ago has failed, because to state the obvious, new terrorist organisations, notably Islamic State, have emerged from the chaotic vacuum of war, replacing al Qaeda with an even more brutal style of terror, especially in Syria.

It is estimated that at least 1.3 million lives have been lost and that almost $2 trillion has been spent on the ongoing "war on terror", though President Barack Obama does not use the term.

The tragedy of the reaction to 9/11, as well as that staggering death toll, is that the West does indeed no longer clearly retain the moral high ground in the world, much as it believes that it does. That moral high ground is to be mourned, not least because it kept us safe and secure.

It's worth remembering, for example, that although hawks like to point out that 9/11 happened before the invasion of Iraq, the UK, for example, was never an al Qaeda target before the Iraq war.

Further, the West has in the past 15 years done virtually nothing to promote a peace settlement between the Israelis and the Palestinians, progress on which could have done so much to ease Muslim suspicion over US and European foreign policy.

On that terrible day in September, 15 years ago, you would have either to be a saint or have a heart of stone not to seek some kind of retribution, or at least a reordering of the West's allies.

Yet today, in London as it braces itself for what authorities say is another probable terror attack, it's easy to reflect back on the "war on terror" with scepticism and even sadness.