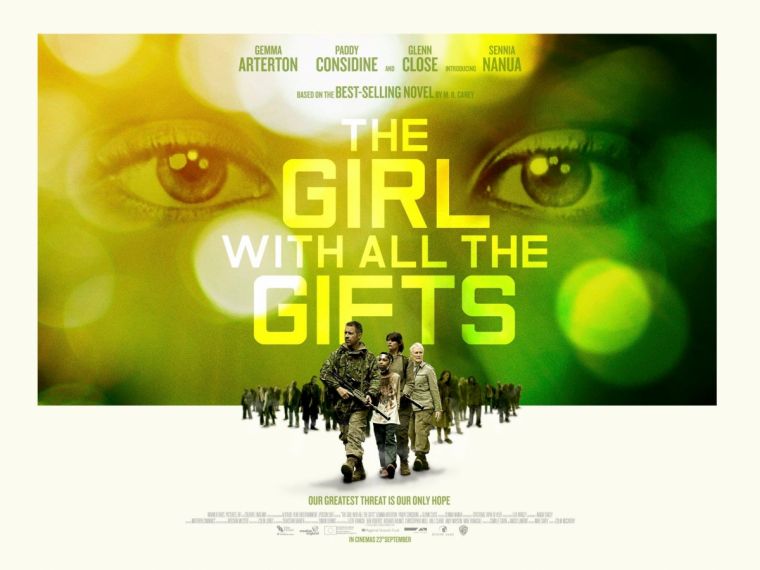

The Girl With All The Gifts review: Zombie kids and a new kind of hope

You've got to work pretty hard to make an apocalyptic zombie thriller feel remotely original these days. The cinema has been saturated with tales of the undead for the past couple of decades, with movies as diverse as World War Z and Shaun of the Dead (and that's not even to mention TV sensation The Walking Dead). Yet new movie The Girl With All The Gifts does manage to breathe some new life into an apparently dying genre by casting a child in a terrifyingly complex central role.

The film rewards those who enter with little prior knowledge of the story, so we'll stick to the bare bones. Melanie (wonderfully gifted newcomer Sennia Nanua) wakes up in a high security underground facility, in which adults treat her with a fear and disgust that she doesn't understand. The worst offender is a nasty army sergeant played by Paddy Considine, but she has also drawn the creepier attentions of Glenn Close's inscrutable scientist. Her only friend seems to be her teacher Miss Justineau (a brilliantly sympathetic Gemma Arterton), who can't accept the awful treatment Melanie receives, even though she knows there's a terrible reason behind it.

Outside the complex there's a world-ending zombie apocalypse breaking out, and before long these four characters are thrust out of the safety of their bunker, and into a dangerous journey across the open countryside. All of this is pretty much par for the genre, and in such a crowded market it's impossible for the movie not to occasionally evoke others. At moments we're in the brilliant Children of Men, at others we trip into 28 Days Later territory, both highly-acclaimed films, but which have broken most of this ground already. Yet at still other times the film does manage to be genuinely original, and it's at these moments that its most interesting themes are explored.

As a culture we're obsessed with zombies, partly because they embody our fears about both the future and the present. But at times we're also terrified of our children; witness the demonisation of young people by tabloid newspapers. When The Girl With All The Gifts juxtaposes these two ideas, it begins to ask big questions about how we treat our young, and how the selfish acts of previous generations have potentially scuppered their future. Melanie suffers unspeakable treatment through much of the movie, and while at first we flinch at how Considine and others relate to her, as the story unfolds we come to the disturbing realisation that we'd probably be on his side. Worse still, when Close's character reveals her terrible intentions for Melanie, we again find ourselves in a terrible moral conflict between doing what's right and our own self-preservation.

The other interesting thing that the film offers is a different definition of hope. Of course, as with most films in the genre, the story involves a group of survivors heading for a place of refuge, but as things progress another vision of the future emerges; one which doesn't place humanity at the top of the tree; which doesn't define hope in terms of humanity's continued prosperity. It's an unusual idea to explore, but it has more in common with the biblical perspective than the modern cultural paradigm. What if it isn't all about us, the movie dares to ask. It's a fine question for Christians to pose too.

It's a naturally gory, and at times chilling, watch, so I'm not about to recommend it for youth group socials. Yet The Girl With All The Gifts is a fine piece of film-making, and one with enough brains to keep viewers in a reflective mood long after the images of zombie battles have faded.

The Girl with All the Gifts is in UK cinemas from September 23.

Martin Saunders is a Contributing Editor for Christian Today and the Deputy CEO of Youthscape. Follow him on Twitter @martinsaunders.