Sex and violence in films are not the problem

With Oscar season approaching, there is only one person to speak to about a Christian perspective on the film industry. Dr Ted Baehr is the head of the Christian film review website MovieGuide.

Their reviews rate films based not only on overall quality of filmmaking, but also the nature of the dominant worldviews and whether they cross any boundaries when it comes to things like nudity, bad language and violence.

Interestingly, none of the best picture nominees in the Oscars this year scored highly with MovieGuide. The best were Captain Phillips and Gravity, which managed scores of minus 1. The Wolf of Wall Street and Dallas Buyers Club received a miserable minus 4. Even the highly praised 12 Years a Slave lost points because of the levels of violence portrayed.

Christian Today talked to Dr Baehr about the use of sex and violence in films, and how Christians should respond to that.

CT: Sex and violence is commonplace in movies today, a far cry from how the movie industry began. How did we get here?

TB: Firstly, everything increased in the mid-1960s with the studios' dropping of the Motion Picture Code. Prior to the 1960s, from 1933-1966, there was agreement between the studios to avoid what Louis B Mayer called "a race to the bottom".

There would be action and violence, but there wouldn't be violence in some way so that young people would want to copy it. There would be romance but there wouldn't be things that would drive people to do anything nefarious.

All of that was dropped in 1965. In 1965 you had 100% of the films being broad audience, even with tough subjects like Bridge over the River Kwai, which is a great film where violence was not glamorised.

Three years later, you went from "The Greatest Story Ever Told" to the first sex and Satanism film, you went from "The Sound of Music" to the first X rated ultra-violent movie.

CT: What about how things have moved down the ratings? We've seen studies saying that violence in PG-13 rated films has tripled since 1985, when PG-13 was instituted.

TB: There has been a PG-13 drift - and Harvard and a couple of other universities started reporting on this 4 to 5 years ago. We did a study on the way that violence affects kids and Bill Clinton happened to see it on TV. He required that theatres checked the ages of kids going to R-Rated movies. When they did that, the R-Rated movie market started to die. So you went from 82% of movies being R-Rated to 40% and now it's even less than that.

So what happened is the movie producers began shifting the violence and the language. Because the R-Rated market was decreased because of carding, violence and language has been moved. This is an ongoing trend, and the question is how are we going to nip this in the bud, or how are we going to get parents to teach their kids to be media wise?

CT: What would you say is the cause of this increase? What do you think has led people to put more violence and sex in films?

TB: Well we just had a study that recently confirms that films with lots of sex and violence actually don't make as much money as those that do. The leading market that's important for box office numbers is women. And women don't want to watch films with lots of violence or sex scenes comparing them to some lithe beautiful girl who does things that they're not willing to do. The women driving the box office has decreased the demand for sex and violence.

If you look at the studio that produced the most violence, that's Weinstein, it has the smallest profit margin. The studio with the least violence is Pixar, and they make the most money.

Why does it happen? Why is there more violence in films other than the fact that these producers no longer have the R-Rated movies to exorcise their demons in? They think this is part of their art and they want their art to triumph.

Often filmmakers want to do things that are against the best interests of the studios. A friend of mine was head of the studio that did a film called Rain Man, about an autistic person who was played with Dustin Hoffman alongside Tom Cruise.

He wanted to make this film because his brother had the syndrome, and his brother could remember things very well, and he wanted to show how these people were just people like everyone else.

But Tom Cruise went on a binge of saying the F-word in one particular scene, and it shut the film down to the audience that might have been open to that message.

We see this all the time. Paramount Pictures is fighting to tone down Noah to get it a broader audience. Columbia pictures wanted to make a kids adventure film called Anaconda about these big snakes. They made the director sign a contract demanding that there be no salacious sex or violence, only for them then to get film coming back with both those things in there.

So the studio executive flew down there and told them: "This is a rubber snake movie! We're making this for teens! We don't want any sex and violence."

The studio wants to make money, but the director thinks he's being artistic by showing another bullet wound or blowing up somebody's face or head or body, and a new way of producing more blood and gore.

The problem is that a number of children are susceptible to it. From hundreds of thousands of studies, we know 7-11% are susceptible in such a way that they want to go out and mimic the violence that they have seen.

When they interview these kids in prison who've shot people, they say, 'We thought it would be like a video game. We thought they would get up again.'

CT: What would you say is the effect of this kind of violence on wider society, not just those who are particularly susceptible?

TB: Well let's be clear, the impact of the violence goes far beyond those who are susceptible, and we should be clear also that the level of susceptibility changes depending on the subject you're talking about.

My alma mater, Dartmouth College, did a study recently that revealed for drugs its 25%, and about 31% for sex. They used to call it sin, but now we just talk psychologically with different people with different propensities.

It corrupts the overall nature of society, so they can be desensitised and don't care anymore, which leads to people allowing children and old people to be killed on the altar of expediency and materialism. We have a whole wide range of impacts on a society that no longer cares about the value of human life.

A friend of mine from India who became a Christian was talking about this. He was saying how in India human life is viewed as being worth so little because they don't see how we're made in the image of God and that we were worth so much that Jesus Christ died for us.

CT: How would you like to see Christians respond to this issue, both as individuals and in terms of the Church more broadly?

TB: Well firstly, I was just on a radio programme where they were blaming the parents about these problems. Parents have a hard time these days because usually both of them are working, usually they're struggling and they don't know where to go. There are the tools to teach children how to be media-wise.

I helped put one together with the TV department in the City of York University in the late seventies. We got 60 professors together to help create the first media literacy course, and now most other media literacy courses have developed from there.

I was speaking in Parliament in the early 90s on this topic. You need to get media literacy into schools, and churches need to teach it on a much more biblical basis.

We've seen some churches take this up. I've seen this much worse in the UK and US, than in countries like say Germany or Korea.

The key thing is, policy wise, we need churches to teach media wisdom to more young people, and we need the ratings authorities to bring the ratings into line with what we know about susceptibility issues.

If we teach media wisdom from an early age we can avoid situations that we've seen, like the Bulger killers, and other such horrific incidents like that.

CT: Do you believe then that Christians creating films should eschew violence and sex in general, or is there a more nuanced approach?

TB: Well conflict is driven by violence and romance and all of that sort of thing. I was once on a Focus in Family programme where someone called in and asked about a character and why they lied, and that surely they should be ashamed of themselves. And I replied and explained that the lie created the plot problem, which allowed the character to solve it.

The problem isn't violence itself, it's when you put violence into a film in such a way that people want to copy it. So that's why I brought up Bridge over the River Kwai, and films like Schindler's List are things we've praised. It's all about how you present the violence and what angle you put on it, and how that leads onto scripts of behaviour, and how we can control those scripts of behaviour.

CT: Do you think that violence and sex in film are similar kinds of problems, or are there important differences there?

TB: Well CS Lewis had that great analogy that gluttony is sin, but eating is wonderful.

The problem isn't that we have sex and romance and adventure and violence in films. I have no problem with those sorts of things being in films, my father was a cowboy star.

It's about how we portray these things, and part of that is down to the writer, but it's also to do with the reader and the consumer of media. It's their job not to get hooked on these things in such a way that they become purveyors of these types of behaviour themselves.

In the US I was the head of two major universities, and I spent a great deal of time teaching people how to read the written word, and I love that and that's why I've written 40 books on it.

But we don't teach people about how to watch the visual media, and it's the visual media that is the dominant force in our society right now. So I think people need to understand the power of the visual media.

For example, with the heart drug Lipitor, the commercial they had for it in the US shows a man struggling to get out of bed, chest pains etc. and then he takes the drug and all of a sudden he's dancing with his wife on a south sea island.

So I went and took that drug, I got my doctor to prescribe it for me, but then after taking it I had chest pains and leg cramps and my son had to rush me to the emergency room. It turns out a certain percentage of people react badly to Lipitor, but you don't get that from the commercials. The media just plays to your emotions. It doesn't tell you all the chemical ingredients and all the possible side effects.

CT: Do you think there is a disconnection between the way sex and violence are each treated as subjects in the American rating system? Sex scenes are rated very differently depending upon whether men or women are being focused on.

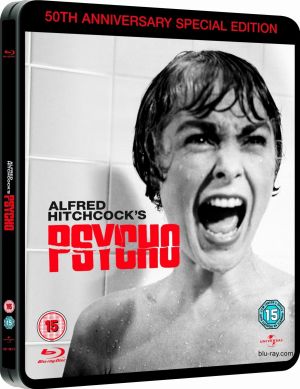

TB: Well I'm a fan of the old system, and I think the modern system is deceptive. You certainly had amazing films during that period. The Hitchcock films for example. There's been three remakes of Psycho since, and they've all been terrible.

The modern system is more like a system of 'we'll give you water, and it's going to be poisonous but we'll put in red food colouring so you know it's poisonous'. But the fact is some people are still going to drink it because even though they know it's poisonous, they want to see how poisonous it is, and how much they can stand. It attracts the very people you're trying to keep away.

In terms of the issues of different treatments of sex and violence you bring up, you know we can deal with them on a Christian level or sociological level. In Christian issues, you know I grew up a pagan, my father was a cowboy star, I did drugs with my father, I had all the one night stands you could have until I was 28, and I was grateful that Jesus rescued me from all that, and the good news is having a wife and four children and not having those propensities that will just lead you down the primrose path.

On that road you just think if you can just have one more drug hit or one more sexual experience you'll be happy, but you're not because you find out you've just got to have one more to be happy.