Scientists in Germany move closer to tapping nuclear fusion for clean energy

With just one flip of a switch, scientists in Germany on Wednesday took the world a major step closer to harnessing a clean form of nuclear energy.

In an event witnessed by no less than German Chancellor and PhD physicist Angela Merkel herself, researchers from the Max Planck Institute in Greifswald switched on an experimental nuclear fusion reactor formally known as the Wendelstein 7-X stellarator.

This state-of-the-art device, which costs around $435 million and took nine years to construct, is being utilised specifically to test if similar fusion reactors can be used in the future to generate clean energy from nuclear fusion.

The researchers specifically injected a small amount of hydrogen into a doughnut-shaped device. Afterwards, they zapped it with heat equivalent to the one generated by a combined 6,000 microwave ovens.

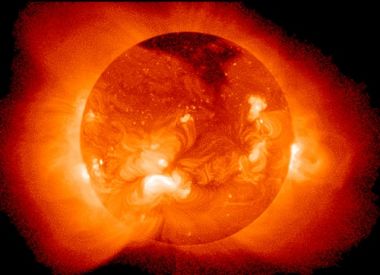

The end product: a super-hot gas known as plasma. This gas was so volatile that it lasted only for a fraction of a second before cooling down again.

This moment might be fleeting, but Robert Wolf, a senior scientist involved with the project, said the start of their experiment was a success.

"Everything went well today. With a system as complex as this you have to make sure everything works perfectly and there's always a risk," Wolf told The New York Times.

The researchers painstakingly took years to find a way to cool the complex arrangement of magnets required to keep the plasma floating inside the stellarator.

"It's far harder to build, but easier to operate," Thomas Klinger, who heads the project, also told The New York Times.

Why is this experiment important? It helps scientists understand more how to generate potentially massive amounts of energy from nuclear fusion, which creates a single heavy nucleus from two lighter nuclei.

The researchers agree that it might take decades for nuclear fusion to be fully tapped for clean energy, but they are taking it one step at a time to reach this goal.

Wolf said his team will try to keep the plasma stable for 30 minutes by gradually increase its temperature.

"If we manage in 2025, that's good. Earlier is even better," he said.