Rare astronomical spectacle: Space scientists witness 2 exploding stars

Every night, we see an uncountable number of stars twinkling in the sky. But we have never seen with our naked eyes a supernova — an exploding star.

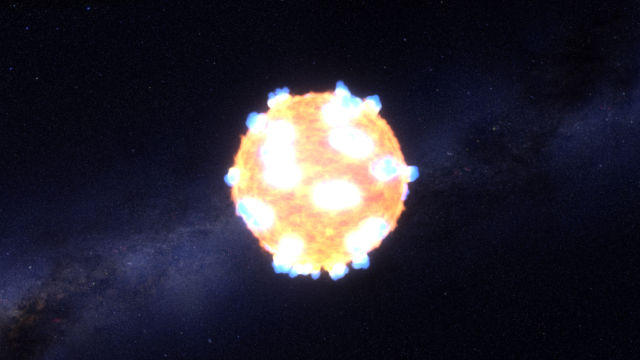

For the first time ever, an international team of space scientists, led by astrophysics professor Peter Garnavich of the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, was able to witness this rare astronomical spectacle: the extremely bright moment when a star goes supernova in visible light.

The space scientists were able to do this with the help of the Kepler space telescope. They started off by analysing data from a three-year period, when the Kepler telescope was able to capture images every 30 minutes, covering over 500 galaxies and 50 trillion stars.

After analysing the data, the researchers narrowed down their points of interest: the two supernovae KSN 2011a and KSN 2011d. The first one is located some 700 million light-years away, with a star nearly 300 times the size of the sun.

The second one was spotted 1.2 billion light-years away, with a star around 500 times that of the sun.

"In order to see something that happens on timescales of minutes, like a shock breakout, you want to have a camera continuously monitoring the sky," Garnavich said in a statement, as quoted by CNET.com.

"You don't know when a supernova is going to go off, and Kepler's vigilance allowed us to be a witness as the explosion began," he added.

The two supernovae were both found to have emitted the same amount of energy, although it was only KSN 2011d that was followed by a shockwave or shock breakout, which lasted for 20 minutes.

The research team thinks that KSN 2011a did not exhibit such a shockwave because gas cloud around the star absorbed or masked the shock breakout.

"That is the puzzle of these results," the lead researcher explained. "You look at two supernovae and see two different things. That's maximum diversity."