Can God still love us if he allows us to suffer?

Dr Vince Vitale began his study of philosophy as an undergraduate at Princeton University and completed his PhD at the University of Oxford, specialising in the problem of suffering and evil. Working as an itinerant speaker with the Zacharias Trust and as team director of the Oxford Centre for Christian Apologetics, Vince has, in the fields of both academia and ministry, dealt extensively and profoundly with the question of God and suffering.

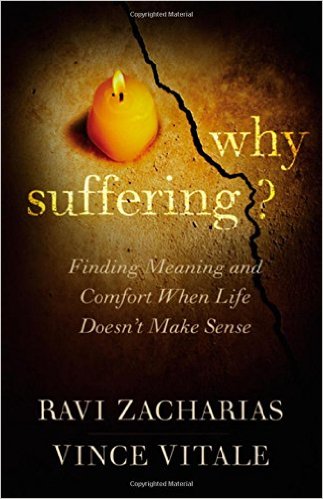

Vince has recently released a co-authored book with Ravi Zacharias, Why Suffering?: Finding Meaning and Comfort When Life Doesn't Make Sense. Here, he tackles some of the big questions:

How did you come to know Christ?

I wasn't a Christian when I showed up at Princeton University as a freshman. I was interested, but I had lots of questions. I was studying philosophy, and I just didn't think Christianity could hold up intellectually. Two guys whom I played soccer with were involved in a Christian community and they invited me along. They and others listened to my questions, answered many of them, and day by day showed me what it looked like to follow Jesus with integrity.

Eventually, I had to admit that the intellectual case for Christianity was far stronger than I ever could have imagined. And as a result I had to admit that my resistance to Jesus Christ had a lot more to do with my heart than with my mind. The truth is I preferred to be my own god. As Nietzsche put it, "If there were gods, how could I bear not being a god?" I accepted a challenge to read the Bible, and as I got to know the person of Jesus, my heart was humbled to see the life I was made for and how different it was from my own. For the first time in my life I knew I needed a savior. It was near the end of my freshman year that I first knew God – not just about God, but God himself – and desired to trust him. I was alone in my dorm room, but I exclaimed out loud, "Oh my gosh, this really happened!"

What motivated you to write Why Suffering? with Ravi Zacharias?

It is common to think there is only one or two Christian responses to the problem of suffering. It is common to think there is nothing new to be said on the topic. It is common for a sharp division to be made between responding to the question of suffering intellectually and responding to it emotionally.

As Ravi and I shared conversations on this topic, we found that we were united in wanting to question all three of these assumptions. We wanted to write something that would be helpful for seekers and Christians alike, for those with intellectual questions and for those who are hurting. We wanted to help show that the intellectual and emotional challenges are deeply related, and that there are not just one or two Christian responses to suffering but rather the variety of responses one would expect from a God who loves each and every person and desires to meet us amidst the great variety of circumstances and challenges we find ourselves in.

Do you think the problem of pain is the greatest obstacle to belief in Christ?

For many people, I think it is. It is such a serious objection because it strikes at the very heart of the gospel: Can God still love us if he allows us to suffer?

In the book, Ravi and I suggest that there are numerous responses to this objection – some very old, some newer – and that just as a multiplicity of witnesses can strengthen a case in a law court, the multiplicity of responses to the problem of suffering should strengthen our confidence in the goodness of God.

But while pain can be a great obstacle, it is also one of the greatest reasons to turn to God. The more seriously we take the problem of suffering – indeed the more seriously we take the people who suffer – the more we will be led to trust the God who can do something about it.

What do you think of Stephen Fry's comments that God must be "utterly evil, capricious and monstrous" if he exists? Does he have a valid point?

There appears to be a lot of emotion behind Stephen Fry's comments, and I think all of us can sympathise with that. In fact Jesus himself wept at the tomb of a good friend, and the night before Jesus died he said "my heart is overwhelmed with sorrow, even to the point of death."

I think the valid point that Stephen makes is that there are things in this world that are utterly evil. And of course that is part of the Christian story, that when we abuse our free will and turn away from what is good and just, the result is evil and suffering – we all can attest to the truth of that. So I want to agree with Stephen Fry that there are things in this world that we need to be able to point at and say, objectively and truly, that is "utterly evil."

As a Christian, I believe I can make a moral claim about such things because there is an objective moral law, and I believe there is an objective moral law because there is a divine moral law-giver.

Once you do away with God, I don't know where one is supposed to find an objective, stable grounding for the very moral claims that Stephen Fry needs in order to object to God. I think Stephen actually needs to assume the existence of God in order to make the argument that he thinks disproves God.

What are some of the new approaches you discuss in the book?

There are several. One of them suggests that when we wish for another world – a very different world that does not include the possibilities for suffering – we may unwittingly be wishing ourselves out of existence. And if God's deep desire is to love you and me and every person we see walking down the street, and to call each of us into relationship with himself, then that complicates the question of what sort of world God might allow to exist.

In another new approach we make an analogy between divine creation and human procreation, and we ask those who think evil disproves God to consider the following question: If it is immoral to create beings in an environment that includes the possibility of serious suffering, then is it immoral for human parents to have a child? We suggest that the same reasons for thinking having a child can be an act of love are also reasons for believing divine creation can be an act of love.

We also take a comparative worldview approach in the book. Criticism without alternative is empty. If one rejects Christianity's response to suffering, one has to ask what alternative responses are available. After looking at responses from Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, and naturalism, we suggest that the Christian response stands tall above any other teaching on pain and suffering.

What does someone need when they are experiencing suffering?

The challenge, I find, is that what each person needs when suffering is very personal. There is no one-size-fits-all. I once responded to my Aunt Regina's questions about suffering with a more philosophical answer, and she responded, "But Vince, that doesn't speak to me as a mother." Since that conversation I have listened and prayed much longer before thinking I know what someone needs.

Ultimately, what we need is the presence of a loved one. And when we have the chance to be that loved one for another, our temporary presence can act as an invitation to a life with One who is always present. One of the greatest gifts of the Christian life is that you never need to wonder if a loved one is near; you never need to wonder if a loved one understands. That Person is always with you, even dwelling within you.

How is Christianity unique in the way it approaches suffering?

In a number of ways. Many ways of seeing the world assume that if you are suffering, it is your fault. Jesus says otherwise. While suffering can be traced back to humanity's fall into sin, Jesus is clear that we cannot assume from the fact that a person is suffering that it is their fault or that they are being punished. A second distinctive of the Christian response to suffering is this: God promises that one day he will wipe away every tear. What an amazing claim, that God himself will wipe away our tears.

And perhaps most unique is that the Christian God chose to suffer with us. Suffering's greatest cruelty is its isolation. The Christian never suffers alone. Ironically, Nietzsche may have said it best: "The gods justified human life by living it themselves – the only satisfactory [response to the problem of suffering] ever invented." Nietzsche was speaking of the ancient Greeks and remarkably never made the connection to Christianity. I am very pleased to agree with him and then point emphatically to the cross of Jesus Christ, to the cross of the only God loving enough to suffer with us and for us.

Why would you recommend the Why Series?

Suffering is a question that is unavoidable, and therefore we all have to take it seriously. We will be addressing it not just at an abstract level but at a personal level that all people, whatever their beliefs or background, can relate to.

Happening this Saturday, May 7 in London, the Why Series is a new annual event addressing a key 'why' question. Amy Orr-Ewing, Michael Ramsden, Vince Vitale and Nabeel Qureshi will be exploring many different aspects of the dilemma of God and suffering. Vince will be addressing suffering and the love of God. You can book your place here.